WASHINGTON, DC: Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali on Faith and Society

By Andrew Harrod

http://www.religiousfreedomcoalition.org/

May 1, 2014

In this article, Pakistani-born Church of England Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali gives an interesting analysis on society's need for faith and right religion, particularly with respect to Christianity and Islam.

In this article, Pakistani-born Church of England Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali gives an interesting analysis on society's need for faith and right religion, particularly with respect to Christianity and Islam.

“Secularism results in totalitarianism…wherever it is tried” leaving “no other answer” for free societies outside of religion, Church of England Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali stated recently at Georgetown University. Faced with this need for faith, the Pakistan native Nazir-Ali offered illuminating comments on right religion on the basis of his mixed Muslim-Christian familial background and theological studies.

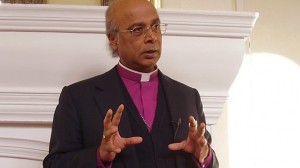

Michael Nazir-Ali

Nazir-Ali addressed “Christian-Muslim Relations: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow” on April 29, 2014, at Georgetown’s Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding (ACMCU). While recognizing the “personal dimension of the spiritual,” Nazir-Ali focused his comments on religion’s social aspects as a “force that binds people together.” Thereby Nazir-Ali posed the question of whether free societies can “legitimize everything,” with welfare systems marginalizing religion.

Spiritual values such as personal happiness “are not things that the welfare state can provide,” he countered. Rather, a “prophet has an obligation to society” in contrast to a mystic, Nazir-Ali noted in discussing Muslim accounts of Islam’s prophet Muhammad visiting heaven by night. Unlike a prophet, a mystic would never have returned to Earth from God’s glorious presence.

Whole societies owed their character to faith foundations. Nazir-Ali considered the modern United Kingdom with its humanitarian values such as universal education and the Middle East “impossible to think of” without Christianity and Islam, respectively. A “particularly Christian, Victorian milieu,” meanwhile, deluded Charles Darwin into believing that his evolutionary theories would have no impact on Western culture.

Nazir-Ali recognized a criticism of “painting a very rosy picture of religion,” for “religions can and do go wrong very badly.” Here Nazir-Ali cited rising “Hindu chauvinism” in India as well as sectarian opposition to his personal involvement in impartially delivering humanitarian aid to Bosnia’s warring faith communities in the 1990s. Religions accordingly “need to be accountable in our world…at the bar of world opinion” rather than defining beliefs and behaviors as solely matters of internal faith doctrine.

Similarly “religions need to be accountable to one another,” in a substantial, and not a “kissy-kissy dialogue.” Nazir-Ali had acted accordingly in conjunction with Cairo’s Al Azhar University, Sunni Islam’s leading theological authority. Thereby Nazir-Ali had discussed the Danish Muhammad cartoons controversy and Abdul Rahman, an Afghan convert to Christianity threatened with execution under Islamic apostasy laws.

Dialogue had particular importance for Christianity and Islam, “for better or worse, the two great missionary faiths in the world today.” As in the past, these two faiths live “cheek by jowl,” raising the issue of whether they will be “good neighbors,” Nazir-Ali observed. Christians and Muslims “have a lot of experience to call upon” in this respect, both good and bad.

On the positive side, Muhammad’s Charter of Medina establishing the first Muslim community appeared to Nazir-Ali as “quite a remarkable document.” “At least in one reading,” he optimistically proclaimed, the charter conferred equal rights and responsibilities upon both Muhammad’s Muslim followers and Medina’s Jewish inhabitants. Thus Nazir-Ali always asked Muslims advocating a Muslim state whether they would emulate the first Muslim society in Medina. Nazir-Ali also cited Islamic traditions exempting Christian areas of Ethiopia from Islamic jihad conquests due to the refuge offered Muslims fleeing pagan persecution in Mecca during the first hijra in 615.

Yet Jewish-Muslim relations, “more up and down” in comparison with historic Christian-Muslim relations, ultimately soured in Medina. Conflict with the Jews led to their expulsion by Muslims, who also “entirely eliminated” one Jewish tribe, the Banu Qurayza. The Muslims later conquered one of the expelled tribes, the Banu Nadir, in their new home of Khaybar oasis and imposed a tribute payment. The Banu Nadir thus modeled future relations between Muslims and non-Muslim dhimmi subjects that is a “problem for common citizenship” today, whatever dhimmitude’s past merits. Even this limited Islamic tolerance in the Arabian Peninsula ended under Muhammad’s second successor, Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab, in the midst of various conflicts. He expelled Khaybar’s Jews as well as a Christian community in Najran, the former going largely to Jericho, the latter to Syria.

In contrast to such conflict, Islamic civilizational achievements often resulted from Jews, Christians, and Muslims cooperating. Institutions translating philosophical works such as the famed ninth-century House of Wisdom under the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad “were staffed almost entirely by Christian clergy.” Medical texts from this era, for example, remained in use at Oxford University until the 18thcentury. Along with European Arab communities such as in Spain, Jewish traders as well transmitted knowledge from Muslim societies to Christendom, giving Muslim thinkers like Ibn Rushd Hebraized names (Averroes) in the process.

That today “radical Islamism has only to do with grievances” Nazir-Ali described as mistaken. Historic experiences like imperialism did affect Muslim outlooks while some young Muslim males today “have just enough education to know that they are not getting what they deserve.” Yet a “jumped up Turk” from the Osmanli tribe (“Never ignore small tribes,” Nazir-Ali commented) founded the Ottoman Empire’s caliphate. Even though, contrary to some Islamic caliphate understandings, the Ottomans did not descend from Muhammad’s Arab Quraish tribe, they claimed a right to Islamic rule due to an ability to wage jihad.

A “strong advocate for religious freedom in every part of the world,” Nazir-Ali demanded that “persuasion, not coercion” define religion’s necessary role in society. This necessitated universal “commitment to fundamental freedoms” and not just “tit-for-tat” reciprocity with a mosque built in a majoritarian-Christian country balancing a church in a majoritarian-Muslim country.

Nazir-Ali noted that Judeo-Christian traditions were the root of free societies not just in the West but also Western-influenced countries like India. Muslim countries like Afghanistan could meanwhile use “their own institutions” (e.g. Loya Jirga) “to promote democratic ideals,” even as Islamic extremism “has obscured…debate about principles of movement” in sharia’s development.

For a free society, though, “it is not enough just to count votes,” Nazir-Ali warned against a “tyranny of the majority” with countries like Egypt in mind. Thus brief Muslim Brotherhood (MB) rule made Egyptian Christians and elite members of society “almost euphoric” at a military-led MB downfall, exhibiting in Egypt a “deep sort of fault line.” Egyptian Christians “were dancing” after the military intervention, audience member Professor Yvonne Haddad of ACMCU concurred. “We must have some safeguards” such as a bill of rights, Nazir-Ali noted, “indeed for the sake of democracy.”

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, however, appeared for many Muslims as “instituted specifically to contain Muslims,” Haddad observed. The Declaration’s recognition of a “freedom to change…religion” in Article 18 allowed Christian missionaries “coming through the back door” after Western imperialism’s end, Haddad elaborated. Similarly the “Gospel of democracy” under American leaders like George W. Bush seemed to undermine Muslim society, presenting therefore a source of Muslim anger along with Israel.

Thus, in a humanity previously noted as “hard-wired for faith,” not all faiths equally answer Nazir-Ali’s call for universal freedom, something necessary for human flourishing as his own discussion of Islamic history indicates. While Nazir-Ali recognizes that a Judeo-Christian outlook frees not just spiritually, his comments show that Christianity’s great theological competitor, Islam, has a more mixed record towards individual human dignity. Islamic religious repression in regime-changed Iraq and Afghanistan demonstrate that here and elsewhere Islamic faith-based free societies equivalent to historically Christian societies (and Israel) have yet to develop. Nazir-Ali’s reference to “Hindu chauvinism” indicates Indian democracy’s struggle in this respect as well.

Whether adherents of Islam or other faiths will heed a “bar of world opinion” over received religious doctrines depends upon recognition of a natural, universal moral law. While Biblical belief proclaims such a relationship between reason and religion for human beings “created…in the image of God” (Genesis 1:27), other faiths like Islam do not necessarily accept this postulate. Even as Christians and others face increasing secular assaults on religious freedom in the West, freedom and faith abroad will remain imperiled.

END