The Trouble With Church Preservation

by Kim A. O'Connell

The Atlantic Cities

http://www.theatlanticcities.com/arts-and-lifestyle/

November 2011

When it comes to the holy trinity of art, architecture, and religion, few buildings are more significant than the 1898 Methodist Church in Norwalk, Connecticut. Anchoring a main street, the Romanesque-style church features a stained-glass rose window designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany himself. The founders of American Methodism preached there. Given its prominence and pedigree, should the church's governing body be allowed to sell the building for development, as it is currently trying to do?

When it comes to the holy trinity of art, architecture, and religion, few buildings are more significant than the 1898 Methodist Church in Norwalk, Connecticut. Anchoring a main street, the Romanesque-style church features a stained-glass rose window designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany himself. The founders of American Methodism preached there. Given its prominence and pedigree, should the church's governing body be allowed to sell the building for development, as it is currently trying to do?

The U.S. Constitution, according to many observers, says yes, but historic preservationists beg to differ. Who decides?

In cities nationwide, churches are struggling to maintain the physical plant. Congregations are dwindling, budgets are tight and buildings are becoming aging white elephants. Many denominations, perhaps most notably the Catholic Church, are closing and selling off their buildings to stay afloat.

But these old churches are beloved landmarks, whether people worship there or not. Churches are key to a city's architectural character and its social and religious history, preservationists say. Often, these advocates will stamp a capital L on these landmarks through official historic designation. At the state or local level, such designations can limit what happens to church buildings by preventing significant alterations or demolition.

Such limitations, church leaders say, can pose economic hardships that interfere with their constitutional right to the free exercise of religion. A spokesman for the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland, for example, recently characterized the city's effort to landmark six churches as "extremely offensive." Federal and state laws, particularly the Religious Land Use and Institutional Persons Act, protect religious groups from some property use restrictions.

Such limitations, church leaders say, can pose economic hardships that interfere with their constitutional right to the free exercise of religion. A spokesman for the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland, for example, recently characterized the city's effort to landmark six churches as "extremely offensive." Federal and state laws, particularly the Religious Land Use and Institutional Persons Act, protect religious groups from some property use restrictions.

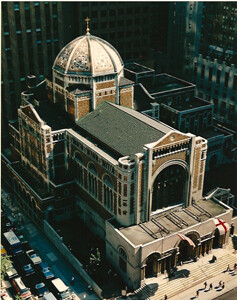

But the case law goes both ways. The most famous federal case on the issue, going back two decades, is St. Bartholomew's Church vs. the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. The church, whose sanctuary is a designated landmark, sought to demolish its adjacent community house to build a high-rise office tower, the income from which would support religious activities. "If we don't have more money," a church official said at the time, "we won't be able to preserve the very building that the preservationists are concerned about: the church sanctuary." The U.S. Court of Appeals ultimately upheld the landmark.

Just a few years later, however, the U.S. District Court of Maryland decided that this precedent did not apply to a case involving a historic monastery in the city of Cumberland. There the court overturned the city's denial of a demolition permit for the monastery, ruling that its free-exercise rights had been violated.

So, cities are often left to decide these issues one controversial case at a time. Two years ago, a D.C. court ruled in favor of the Third Church of Christ, Scientist, whose leaders wanted to raze its hulking Brutalist building, located near the White House, to create a more traditional (and easier to maintain) worship space. The D.C. Historic Preservation Office had landmarked the building - designed by the office of I.M. Pei - in response to the original demo request. Earlier this year, the New York City Council denied a landmark designation for the historic Grace Episcopal Church in Queens after the church cited the financial burden of maintaining the structure according to historic standards.

The challenge for preservationists is coming up with alternatives that protect a church's historic character while providing cost-effective long-term solutions. Sometimes the cure proves as burdensome as the disease. In Philadelphia, the 1849* Church of the Assumption had sold its building to Siloam, a nonprofit HIV/AIDs group, which originally intended to maintain the historic building for its uses - a supposed victory for preservation. Yet this proved economically untenable. Siloam is now trying to sell the building, leading to yet another preservation appeal.

"This trend is accelerating," says architect Richard Wagner, whose Baltimore firm David H. Gleason Associates has adapted historic churches. "When these churches are closed down by their congregations, they're willing to sell it to whoever will pay. These buildings do not have many takers, because they're hard to adapt and have a lot of cubic footage. So you're not left with many options from a preservation standpoint."

Back in Norwalk, where the Methodist church is currently listed for sale at $1.2 million, the Norwalk Preservation Trust is now working with the state to either develop a new program or leverage existing law to save the building.

"These churches were built by congregations who were very proud of them, who created these great architectural works of art," says Trust President Tod Bryant. "They may be difficult and expensive to maintain now, but that's why a greater program to help them do that would be useful. No one's saying they can't worship the way they want to or go bankrupt in the process. But the congregations who built these buildings saw them as part of the worship, and that sentiment should be honored as well."

Maybe whatever happens in Norwalk will help define precedent nationwide. But if the past is any guide - and it always is, as preservationists would say - then this issue will likely stay muddled for some time to come.

END